Please use following for referencing:

Toury, Gideon 1995. "The Nature and Role of Norms in Translation". In idem,

Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam-Philadelphia:

John Benjamins, 1995, 53-69.

© All rights reserved.

Text scanned for educational use, Unit for Culture Research, Tel Aviv

University

(

http://spinoza.tau.ac.il/~toury/works).

Gideon Toury

[Chapter 2]

The Nature and Role of Norms in Translation

However highly one may think of Linguistics, Text-Linguistics, Contrastive

Textology or Pragmatics and of their explanatory power with respect to

translational phenomena, being a translator cannot be reduced to the mere

generation of utterances which would be considered 'translations' within any of

these disciplines. Translation activities should rather be regarded as having

cultural significance. Consequently, 'translatorship' amounts first and foremost

to being able to play a social role, i.e., to fulfil a function allotted by a community

-- to the activity, its practitioners and/or their products -- in a way which is

deemed appropriate in its own terms of reference. The acquisition of a set of

norms for determining the suitability of that kind of behaviour, and for

manoeuvring between all the factors which may constrain it, is therefore a

prerequisite for becoming a translator within a cultural environment.

The process by which a bilingual speaker may be said to gain recognition in

his/her capacity as a translator has hardly been studied so far. It will be specu-

lated upon at some length towards the end of the book (Excursus C). In the

present chapter the nature of the acquired norms themselves will be addressed,

along with their role in directing translation activity in socio-culturally relevant

settings. This presentation will be followed by a brief discussion of translational

norms as a second-order object of Translation Studies, to be reconstructed and

studied within the kind of framework which we are now in the process of

sketching. As strictly translational norms can only be applied at the receiving end,

establishing them is not merely justified by a target-oriented approach but

should be seen as its very epitome.

54 DESCRIPTIVE TRANSLATION STUDIES AND BEYOND

1. Rules, norms, idiosyncrasies

In its socio-cultural dimension, translation can be described as subject to

constraints of several types and varying degree. These extend far beyond the

source text, the systemic differences between the languages and textual tradi-

tions involved in the act, or even the possibilities and limitations of the cogni-

tive apparatus of the translator as a necessary mediator. In fact, cognition itself

is influenced, probably even modified by socio-cultural factors. At any rate,

translators performing under different conditions (e.g., translating texts of

different kinds, and/or for different audiences) often adopt different strategies,

and ultimately come up with markedly different products. Something has

obviously changed here, and I very much doubt it that it is the cognitive

apparatus as such.

In terms of their potency, socio-cultural constraints have been described

along a scale anchored between two extremes: general, relatively absolute rules

on the one hand, and pure idiosyncrasies on the other. Between these two poles

lies a vast middle-ground occupied by intersubjective factors commonly

designated norms. The norms themselves form a graded continuum along the

scale: some are stronger, and hence more rule-like, others are weaker, and hence

almost idiosyncratic. The borderlines between the various types of constraints

are thus diffuse. Each of the concepts, including the grading itself, is relative too.

Thus, what is just a favoured mode of behaviour within a heterogeneous group

may well acquire much more binding force within a certain (more homogene-

ous) section thereof, in terms of either human agents (e.g., translators among

texters in general) or types of activity (e.g., interpreting, or legal translation,

within translation at large).

Along the temporal axis, each type of constraint may, and often does move

into its neighbouring domain(s) through processes of rise and decline. Thus,

mere whims may catch on and become more and more normative, and norms

can gain so much validity that, for all practical purposes, they become as

binding as rules; or the other way around, of course. Shifts of validity and force

often have to do with changes of status within a society. In fact, they can always

be described in connection with the notion of norm, especially since, as the

process goes on, they are likely to cross its realm, i.e., actually become norms.

The other two types of constraints may even be redefined in terms of norms:

rules as '[more] objective', idiosyncrasies as '[more] subjective [or: less inter-

subjective]' norms.

Sociologists and social psychologists have long regarded norms as the

NORMS IN TRANSLATION 55

translation of general values or ideas shared by a community -- as to what is

right and wrong, adequate and inadequate -- into performance instructions

appropriate for and applicable to particular situations, specifying what is pre-

scribed and forbidden as well as what is tolerated and permitted in a certain

behavioural dimension (the famous 'square of normativity', which has lately

been elaborated on with regard to translation in De Geest 1992: 38-40). Norms

are acquired by the individual during his/her socialization and always imply

sanctions -- actual or potential, negative as well as positive. Within the com-

munity, norms also serve as criteria according to which actual instances of

behaviour are evaluated. Obviously, there is a point in assuming the existence of

norms only in situations which allow for different kinds of behaviour, on the

additional condition that selection among them be nonrandom.1 Inasmuch as

a norm is really active and effective, one can therefore distinguish regularity of

behaviour in recurrent situations of the same type, which would render

regularities a main source for any study of norms as well.

The centrality of the norms is not only metaphorical, then, in terms of their

relative position along a postulated continuum of constraints; rather, it is

essential: Norms are the key concept and focal point in any attempt to account

for the social relevance of activities, because their existence, and the wide range

of situations they apply to (with the conformity this implies), are the main

factors ensuring the establishment and retention of social order. This holds for

cultures too, or for any of the systems constituting them, which are, after all,

social institutions ipso facto. Of course, behaviour which does not conform to

prevailing norms is always possible too. Moreover, "non-compliance with a

norm in particular instances does not invalidate the norm" (Hermans 1991:

162). At the same time, there would normally be a price to pay for opting for any

deviant kind of behaviour.

One thing to bear in mind, when setting out to study norm-governed

behaviour, is that there is no necessary identity between the norms themselves

and any formulation of them in language. Verbal formulations of course reflect

awareness of the existence of norms as well as of their respective significance.

However, they also imply other interests, particularly a desire to control behaviour

-- i.e., to dictate norms rather than merely account for them. Normative formula-

tions tend to be slanted, then, and should always be taken with a grain of salt.

1. "The existence of norms is a sine qua non in instances of labeling and regulating;

without a norm, all deviations are meaningless and become cases of free variation"

(Wexler 1974: 4, n. 1).

56 DESCRIPTIVE TRANSLATION STUDIES AND BEYOND

2. Translation as a norm-governed activity

Translation is a kind of activity which inevitably involves at least two languages and

two cultural traditions, i.e., at least two sets of norm-systems on each level. Thus, the

'value' behind it may be described as consisting of two major elements:

(1) being a text in a certain language, and hence occupying a position, or

filling in a slot, in the appropriate culture, or in a certain section thereof;

(2) constituting a representation in that language/culture of another, pre-

existing text in some other language, belonging to some other culture and

occupying a definite position within it.

These two types of requirement derive from two sources which -- even

though the distance between them may vary greatly -- are nevertheless always

different and therefore often incompatible. Were it not for the regulative

capacity of norms, the tensions between the two sources of constraints would

have to be resolved on an entirely individual basis, and with no clear yardstick to

go by. Extreme free variation may well have been the result, which it certainly

is not. Rather, translation behaviour within a culture tends to manifest certain

regularities, one consequence being that even if they are unable to account for

deviations in any explicit way, the persons-in-the-culture can often tell when a

translator has failed to adhere to sanctioned practices.

It has proven useful and enlightening to regard the basic choice which can

be made between requirements of the two different sources as constituting an

initial norm. Thus, a translator may subject him-/herself either to the original

text, with the norms it has realized, or to the norms active in the target culture,

or in that section of it which would host the end product. If the first stance is

adopted, the translation will tend to subscribe to the norms of the source text,

and through them also to the norms of the source language and culture. This

tendency, which has often been characterized as the pursuit of adequate trans-

lation,2 may well entail certain incompatibilities with target norms and prac-

tices, especially those lying beyond the mere linguistic ones. If, on the other

hand, the second stance is adopted, norm systems of the target culture are

triggered and set into motion. Shifts from the source text would be an almost

inevitable price. Thus, whereas adherence to source norms determines a

2. "An adequate translation is a translation which realizes in the target language the

textual relationships of a source text with no breach of its own [basic] linguistic system"

(Even-Zohar 1975: 43; my translation).

NORMS IN TRANSLATION 57

translation's adequacy as compared to the source text, subscription to norms

originating in the target culture determines its acceptability.

Obviously, even the most adequacy-oriented translation involves shifts

from the source text. In fact, the occurrence of shifts has long been acknowl-

edged as a true universal of translation. However, since the need itself to deviate

from source-text patterns can always be realized in more than one way, the

actual realization of so-called obligatory shifts, to the extent that it is non-

random, and hence not idiosyncratic, is already truly norm-governed. So is

everything that has to do with non-obligatory shifts, which are of course more

than just possible in real-life translation: they occur everywhere and tend to

constitute the majority of shifting in any single act of human translation, render-

ing the latter a contributing factor to, as well as the epitome of regularity.

The term 'initial norm' should not be overinterpreted, however. Its initiality

derives from its superordinance over particular norms which pertain to lower,

and therefore more specific levels. The kind of priority postulated here is

basically logical, and need not coincide with any 'real', i.e., chronological order of

application. The notion is thus designed to serve first and foremost as an explanatory

tool: Even if no clear macro-level tendency can be shown, any micro-level

decision can still be accounted for in terms of adequacy vs. acceptability. On the

other hand, in cases where an overall choice has been made, it is not necessary

that every single lower-level decision be made in full accord with it. We are still

talking regularities, then, but not necessarily of any absolute type. It is unrealis-

tic to expect absolute regularities anyway, in any behavioural domain.

Actual translation decisions (the results of which the researcher would

confront) will necessarily involve some ad hoc combination of, or compromise

between the two extremes implied by the initial norm. Still, for theoretical and

methodological reasons, it seems wiser to retain the opposition and treat the two

poles as distinct in principle: If they are not regarded as having distinct theoreti-

cal statuses, how would compromises differing in type or in extent be distin-

guished and accounted for?

Finally, the claim that it is basically a norm-governed type of behaviour

applies to translation of all kinds, not only literary, philosophical or biblical

translation, which is where most norm-oriented studies have been conducted so

far. As has recently been claimed and demonstrated in an all too sketchy

exchange of views in Target (M. Shlesinger 1989b and Harris 1990), similar

things can even be said of conference interpreting. Needless to say, this does not

mean that the exact same conditions apply to all kinds of translation. In fact,

their application in different cultural sectors is precisely one of the aspects that

58 DESCRIPTIVE TRANSLATION STUDIES AND BEYOND

should be submitted to study. In principle, the claim is also valid for every

society and historical period, thus offering a framework for historically oriented

studies which would also allow for comparison.

3. Translational norms: An overview

Norms can be expected to operate not only in translation of all kinds, but also

at every stage in the translating event, and hence to be reflected on every level

of its product. It has proven convenient to first distinguish two larger groups of

norms applicable to translation: preliminary vs. operational.

Preliminary norms have to do with two main sets of considerations which

are often interconnected: those regarding the existence and actual nature of a

definite translation policy, and those related to the directness of translation.

Translation policy refers to those factors that govern the choice of text-

types, or even of individual texts, to be imported through translation into a

particular culture/language at a particular point in time. Such a policy will be

said to exist inasmuch as the choice is found to be nonrandom. Different

policies may of course apply to different subgroups, in terms of either text-types

(e.g., literary vs. non-literary) or human agents and groups thereof (e.g., different

publishing houses), and the interface between the two often offers very fertile

grounds for policy hunting.

Considerations concerning directness of translation involve the threshold of

tolerance for translating from languages other than the ultimate source lan-

guage: is indirect translation permitted at all? In translating from what source

languages/text-types/periods (etc.) is it permitted/prohibited/tolerated/preferred?

What are the permitted/prohibited/tolerated/preferred mediating languages? Is

there a tendency/obligation to mark a translated work as having been mediated,

or is this fact ignored/camouflaged/denied? If it is mentioned, is the identity of

the mediating language supplied as well? And so on.

Operational norms, in turn, may be conceived of as directing the decisions

made during the act of translation itself. They affect the matrix of the text -- i.e.,

the modes of distributing linguistic material in it -- as well as the textual make-

up and verbal formulation as such. They thus govern -- directly or indirectly --

the relationships as well that would obtain between the target and source texts;

i.e., what is more likely to remain invariant under transformation and what

will change.

So-called matricial norms may govern the very existence of target-language

NORMS IN TRANSLATION 59

material intended as a substitute for the corresponding source-language material

(and hence the degree of fullness of translation), its location in the text (or the

form of actual distribution), as well as the textual segmentation.3 The extent to

which omissions, additions, changes of location and manipulations of segmenta-

tion are referred to in the translated texts (or around them) may also be deter-

mined by norms, even though the one can very well occur without the other.

Obviously, the borderlines between the various matricial phenomena are

not clear-cut. For instance, large-scale omissions often entail changes of segmen-

tation as well, especially if the omitted portions have no clear boundaries, or

textual-linguistic standing, i.e., if they are not integral sentences, paragraphs or

chapters. By the same token, a change of location may often be accounted for as

an omission (in one place) compensated by an addition (elsewhere). The

decision as to what may have 'really' taken place is thus description-bound:

What one is after is (more or less cogent) explanatory hypotheses, not necessarily

'true-to-life' accounts, which one can never be sure of anyway.

Textual-linguistic norms, in turn, govern the selection of material to

formulate the target text in, or replace the original textual and linguistic material

with. Textual-linguistic norms may either be general, and hence apply to

translation qua translation, or particular, in which case they would pertain to a

particular text-type and/or mode of translation only. Some of them may be

identical to the norms governing non-translational text-production, but such an

identity should never be taken for granted. This is the methodological reason

why no study of translation can, or should proceed from the assumption that the

latter is representative of the target language, or of any overall textual tradition

thereof. (And see our discussion of 'translation-specific lexical items' in Chapter 11.)

It is clear that preliminary norms have both logical and chronological

precedence over the operational ones. This is not to say that between the two

major groups there are no relationships whatsoever, including mutual influ-

ences, or even two-way conditioning. However, these relations are by no means

3. The claim that principles of segmentation follow universal patterns is just a figment of

the imagination of some discourse and text theoreticians intent on uncovering as many

universal principles as possible. In actual fact, there have been various traditions (or

'models') of segmentation, and the differences between them always have implications

for translation, whether they are taken to bear on the formulation of the target text or

ignored. Even the segmentation of sacred texts such as the Old Testament itself has

often been tampered with by its translators, normally in order to bring it closer to target

cultural habits, and by so doing enhance the translation's acceptability.

60 DESCRIPTIVE TRANSLATION STUDIES AND BEYOND

fixed and given, and their establishment forms an inseparable part of any study

of translation as a norm-governed activity. Nevertheless, we can safely assume at

least that the relations which do exist have to do with the initial norm. They

might even be found to intersect it -- another important reason to retain the

opposition between 'adequacy' and 'acceptability' as a basic coordinate system

for the formulation of explanatory hypotheses.4

Operational norms as such may be described as serving as a model, in

accordance with which translations come into being, whether involving the norms

realized by the source text (i.e., adequate translation) plus certain modifications,

or purely target norms, or a particular compromise between the two. Every

model supplying performance instructions may be said to act as a restricting

factor: it opens up certain options while closing others. Consequently, when

the first position is fully adopted, the translation can hardly be said to have

been made into the target language as a whole. Rather, it is made into a model-

language, which is at best some part of the former and at worst an artificial, and

as such nonexistent variety.5 In this last case, the translation is not really

introduced into the target culture either, but is imposed on it, so to speak. Sure, it

may eventually carve a niche for itself in the latter, but there is no initial attempt

to accommodate it to any existing 'slot'. On the other hand, when the second

position is adopted, what a translator is introducing into the target culture

4. Thus, for instance, in sectors where the pursuit of adequate translation is marginal, it is

highly probable that indirect translation would also become common, on occasion even

preferred over direct translation. By contrast, a norm which prohibits mediated

translation is likely to be connected with a growing proximity to the initial norm of

adequacy. Under such circumstances, if indirect translation is still performed, the fact

will at least be concealed, if not outright denied.

5. And see, in this connection, Izre'el's "Rationale for Translating Ancient Texts into a

Modern Language" (1994). In an attempt to come up with a method for translating an

Akkadian myth which would be presented to modern Israeli audiences in an oral

performance, he purports to combine a "feeling-of-antiquity" with a "feeling-of-

modernity" in a text which would be altogether simple and easily comprehensible by

using a host of lexical items of biblical Hebrew in Israeli Hebrew grammatical and

syntactic structures. Whereas "the lexicon ... would serve to give an ancient flavor to the

text, the grammar would serve to enable modern perception". It might be added that

this is a perfect mirror image of the way Hebrew translators started simulating spoken

Hebrew in their texts: spoken lexical items were inserted in grammatical and syntactic

structures which were marked for belonging to the written varieties (Ben-Shahar 1983),

which also meant 'new' into 'old'.

NORMS IN TRANSLATION 61

(which is indeed what s/he can be described as doing now) is a version of the

original work, cut to the measure of a preexisting model. (And see our discussion

of the opposition between the 'translation of literary texts' and 'literary trans-

lation' in Excursus B as well as the detailed presentation of the Hebrew transla-

tion of a German Schlaraffenland text in Chapter 8.)

The apparent contradiction between any traditional concept of equivalence

and the limited model into which a translation has just been claimed to be

moulded can only be resolved by postulating that it is norms that determine

the (type and extent of) equivalence manifested by actual translations. The

study of norms thus constitutes a vital step towards establishing just how the

functional-relational postulate of equivalence (see Chapter 1, Section 5 and

Chapter 3, Section 6) has been realized -- whether in one translated text, in the

work of a single translator or 'school' of translators, in a given historical period,

or in any other justifiable selection.6 What this approach entails is a clear wish

to retain the notion of equivalence, which various contemporary approaches

(e.g., Hönig and Kußmaul 1982; Holz-Mänttäri 1984; Snell-Hornby 1988) have

tried to do without, while introducing one essential change into it: from an

ahistorical, largely prescriptive concept to a historical one. Rather than being a

single relationship, denoting a recurring type of invariant, it comes to refer to

any relation which is found to have characterized translation under a specified

set of circumstances.

At the end of a full-fledged study it will probably be found that translational

norms, hence the realization of the equivalence postulate, are all, to a large

extent, dependent on the position held by translation -- the activity as well as its

products -- in the target culture. An interesting field for study is therefore

comparative: the nature of translational norms as compared to those governing

non-translational kinds of text-production. In fact, this kind of study is absolute-

ly vital, if translating and translations are to be appropriately contextualized.

4. The multiplicity of translational norms

The difficulties involved in any attempt to account for translational norms

should not be underestimated. These, however, lie first and foremost in two

6. See also my discussion of "Equivalence and Non-Equivalence as a Function of Norms"

(Toury 1980a: 63-70).

62 DESCRIPTIVE TRANSLATION STUDIES AND BEYOND

features inherent in the very notion of norm, and are therefore not unique to

Translation Studies at all: the socio-cultural specificity of norms and their

basic instability.

Thus, whatever its exact content, there is absolutely no need for a norm to

apply -- to the same extent, or at all -- to all sectors within a society. Even less

necessary, or indeed likely, is it for a norm to apply across cultures. In fact,

'sameness' here is a mere coincidence -- or else the result of continuous contacts

between subsystems within a culture, or between entire cultural systems, and

hence a manifestation of interference. (For some general rules of systemic

interference see Even-Zohar 1990: 53-72.) Even then, it is often more a matter of

apparent than of a genuine identity. After all, significance is only attributed to a

norm by the system in which it is embedded, and the systems remain different

even if instances of external behaviour appear the same.

In addition to their inherent specificity, norms are also unstable, changing

entities; not because of any intrinsic flaw but by their very nature as norms. At

times, norms change rather quickly; at other times, they are more enduring, and

the process may take longer. Either way, substantial changes, in translational

norms too, quite often occur within one's life-time.

Of course, it is not as if all translators are passive in face of these changes.

Rather, many of them, through their very activity, help in shaping the process,

as do translation criticism, translation ideology (including the one emanating

from contemporary academe, often in the guise of theory), and, of course,

various norm-setting activities of institutes where, in many societies, translators

are now being trained. Wittingly or unwittingly, they all try to interfere with the

'natural' course of events and to divert it according to their own preferences. Yet,

the success of their endeavours is never fully foreseeable. In fact, the relative role

of different agents in the overall dynamics of translational norms is still largely

a matter of conjecture even for times past, and much more research is needed to

clarify it.

Complying with social pressures to constantly adjust one's behaviour to

norms that keep changing is of course far from simple, and most people --

including translators, initiators of translation activities and the consumers of

their products -- do so only up to a point. Therefore, it is not all that rare to find

side by side in a society three types of competing norms, each having its own

followers and a position of its own in the culture at large: the ones that domi-

nate the center of the system, and hence direct translational behaviour of the so-

called mainstream, alongside the remnants of previous sets of norms and the

NORMS IN TRANSLATION 63

rudiments of new ones, hovering in the periphery. This is why it is possible to

speak -- and not derogatorily -- of being 'trendy', 'old-fashioned' or 'progressive' in

translation (or in any single section thereof) as it is in any other behavioural domain.

One's status as a translator may of course be temporary, especially if one

fails to adjust to the changing requirements, or does so to an extent which is

deemed insufficient. Thus, as changes of norms occur, formerly 'progressive'

translators may soon find themselves just 'trendy', or on occasion as even

downright 'passé'. At the same time, regarding this process as involving a mere

alternation of generations can be misleading, especially if generations are

directly equated with age groups. While there often are correlations between

one's position along the 'dated'-'mainstream'-'avant-garde' axis and one's age,

these cannot, and should not be taken as inevitable, much less as a starting point

and framework for the study of norms in action. Most notably, young people

who are in the early phases of their initiation as translators often behave in an

extremely epigonic way: they tend to perform according to dated, but still existing

norms, the more so if they receive reinforcement from agents holding to dated

norms, be they language teachers, editors, or even teachers of translation.

Multiplicity and variation should not be taken to imply that there is no

such thing as norms active in translation. They only mean that real-life situ-

ations tend to be complex; and this complexity had better be noted rather than

ignored, if one is to draw any justifiable conclusions. As already argued (mainly

in Chapter 1, Section 3), the only viable way out seems to be to contextualize

every phenomenon, every item, every text, every act, on the way to allotting the

different norms themselves their appropriate position and valence. This is why

it is simply unthinkable, from the point of view of the study of translation as a

norm-governed activity, for all items to be treated on a par, as if they were of the

same systemic position, the same significance, the same level of representative-

ness of the target culture and its constraints. Unfortunately, such an indiscriminate

approach has been all too common, and has often led to a complete blurring of the

normative picture, sometimes even to the absurd claim that no norms could be

detected at all. The only way to keep that picture in focus is to go beyond the

establishment of mere 'check-lists' of factors which may occur in a corpus and

have the lists ordered, for instance with respect to the status of those factors as

characterizing 'mainstream', 'dated' and 'avant-garde' activities, respectively.

This immediately suggests a further axis of contextualization, whose

necessity has so far only been implied; namely, the historical one. After all, a

norm can only be marked as 'dated' if it was active in a previous period, and if, at

64 DESCRIPTIVE TRANSLATION STUDIES AND BEYOND

that time, it had a different, 'non-dated' position. By the same token, norm-

governed behaviour can prove to have been 'avant-garde' only in view of sub-

sequent attitudes towards it: an idiosyncrasy which never evolved into something

more general can only be described as a norm by extension, so to speak (see

Section 1 above). Finally, there is nothing inherently 'mainstream' about

mainstream behaviour, except when it happens to function as such, which

means that it too is time-bound. What I am claiming here, in fact, is that

historical contextualization is a must not only for a diachronic study, which

nobody would contest, but also for synchronic studies, which still seems a lot less

obvious, unless one has accepted the principles of so-called 'Dynamic Functionalism'

(for which, see the Introduction to Even-Zohar 19907 and Sheffy 1992: passim).

Finally, in translation too, non-normative behaviour is always a possibility.

The price for selecting this option may be as low as a (culturally determined)

need to submit the end product to revision. However, it may also be far more

severe, to the point of taking away one's earned recognition as a translator;

which is precisely why non-normative behaviour tends to be the exception, in

actual practice. On the other hand, in retrospect, deviant instances of behaviour

may be found to have effected changes in the very system. This is why they

constitute an important field of study, as long as they are regarded as what they

have really been and are not put indiscriminately into one basket with all the

rest. Implied are intriguing questions such as who is 'allowed' by a culture to

introduce changes and under what circumstances such changes may be expected

to occur and/or be accepted.

7. "There is a clear difference between an attempt to account for some major principles

which govern a system outside the realm of time, and one which intends to account for

how a system operates both 'in principle' and 'in time.' Once the historical aspect is

admitted into the functional approach, several implications must be drawn. First, it

must be admitted that both synchrony and diachrony are historical, but the exclusive

identification of the latter with history is untenable. As a result, synchrony cannot and

should not be equated with statics, since at any given moment, more than one

diachronic set is operating on the synchronic axis. Therefore, on the one hand a system

consists of both synchrony and diachrony; on the other, each of these separately is

obviously also a system. Secondly, if the idea of structuredness and systemicity need no

longer be identified with homogeneity, a semiotic system can be conceived of as a

heterogeneous, open structure. It is, therefore, very rarely a uni-system but is, necessar-

ily, a polysystem" (Even-Zohar 1990: 11).

NORMS IN TRANSLATION 65

5. Studying translational norms

So far we have discussed norms mainly in terms of their activity during a

translation event and their effectiveness in the act of translation itself. To be

sure, this is precisely where and when translational norms are active. However,

what is actually available for observation is not so much the norms themselves,

but rather norm-governed instances of behaviour. To be even more precise,

more often than not, it is the products of such behaviour. Thus, even when

translating is claimed to be studied directly, as is the case with the use of

'Thinking-Aloud Protocols' (see Chapter 12, Section 3), it is only products

which are available, although products of a different kind and order. Norms

are not directly observable, then, which is all the more reason why something

should also be said about them in the context of an attempt to account for

translational behaviour.

There are two major sources for a reconstruction of translational norms,

textual and extratextual:8

(1) textual: the translated texts themselves, for all kinds of norms, as well as

analytical inventories of translations (i.e., 'virtual' texts), for various pre-

liminary norms;

(2) extratextual: semi-theoretical or critical formulations, such as prescriptive

'theories' of translation, statements made by translators, editors, publishers,

and other persons involved in or connected with the activity, critical ap-

praisals of individual translations, or the activity of a translator or 'school'

of translators, and so forth.

There is a fundamental difference between these two types of source: Texts

are primary products of norm-regulated behaviour, and can therefore be taken as

immediate representations thereof. Normative pronouncements, by contrast, are

merely by-products of the existence and activity of norms. Like any attempt to

formulate a norm, they are partial and biased, and should therefore be treated

with every possible circumspection; all the more so since -- emanating as they do

from interested parties -- they are likely to lean toward propaganda and persua-

sion. There may therefore be gaps, even contradictions, between explicit argu-

ments and demands, on the one hand, and actual behaviour and its results, on

8. Cf., e.g., Vodicka (1964: 74), on the possible sources for the study of literary norms, and

Wexler (1974: 7-9), on the sources for the study of prescriptive intervention ('purism')

in language.

66 DESCRIPTIVE TRANSLATION STUDIES AND BEYOND

the other, due either to subjectivity or naivete, or even lack of sufficient knowl-

edge on the part of those who produced the formulations. On occasion, a

deliberate desire to mislead and deceive may also be involved. Even with respect

to the translators themselves, intentions do not necessarily concur with any

declaration of intent (which is often put down post factum anyway, when the act

has already been completed); and the way those intentions are realized may well

constitute a further, third category still.

Yet all these reservations -- proper and serious though they may be --

should not lead one to abandon semi-theoretical and critical formulations as

legitimate sources for the study of norms. In spite of all its faults, this type of

source still has its merits, both in itself and as a possible key to the analysis of

actual behaviour. At the same time, if the pitfalls inherent in them are to be

avoided, normative pronouncements should never be accepted at face value.

They should rather be taken as pre-systematic and given an explication in such a

way as to place them in a narrow and precise framework, lending the resulting

explicata the coveted systematic status. While doing so, an attempt should be

made to clarify the status of each formulation, however slanted and biased it

may be, and uncover the sense in which it was not just accidental; in other

words, how, in the final analysis, it does reflect the cultural constellation within

which, and for whose purposes it was produced. Apart from sheer speculation,

such an explication should involve the comparison of various normative

pronouncements to each other, as well as their repeated confrontation with the

patterns revealed by [the results of] actual behaviour and the norms recon-

structed from them -- all this with full consideration for their contextualization.

(See a representative case in Weissbrod 1989.)

It is natural, and very convenient, to commence one's research into

translational behaviour by focussing on isolated norms pertaining to well-

defined behavioural dimensions, be they -- and the coupled pairs of replacing

and replaced segments representing them -- established from the source text's

perspective (e.g., translational replacements of source metaphors) or from the

target text's vantage point (e.g., binomials of near-synonyms as translational

replacements). However, translation is intrinsically multi-dimensional: the mani-

fold phenomena it presents are tightly interwoven and do not allow for easy

isolation, not even for methodical purposes. Therefore, research should never

get stuck in the blind alley of the 'paradigmatic' phase which would at best yield

lists of 'normemes', or discrete norms. Rather, it should always proceed to a

'syntagmatic' phase, involving the integration of normemes pertaining to various

problem areas. Accordingly, the student's task can be characterized as an attempt

NORMS IN TRANSLATION 67

to establish what relations there are between norms pertaining to various

domains by correlating his/her individual findings and weighing them against

each other. Obviously, the thicker the network of relations thus established, the

more justified one would be in speaking in terms of a normative structure(cf.

Jackson 1960: 149-160) or model.

This having been said, it should again be noted that a translator's behaviour

cannot be expected to be fully systematic. Not only can his/her decision-making

be differently motivated in different problem areas, but it can also be unevenly

distributed throughout an assignment within a single problem area. Consistency

in translational behaviour is thus a graded notion which is neither nil (i.e., total

erraticness) nor 1 (i.e., absolute regularity); its extent should emerge at the end

of a study as one of its conclusions, rather than being presupposed.

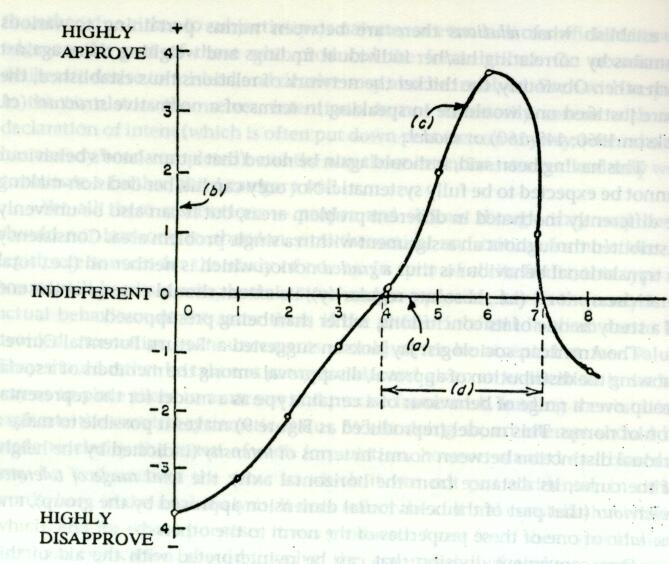

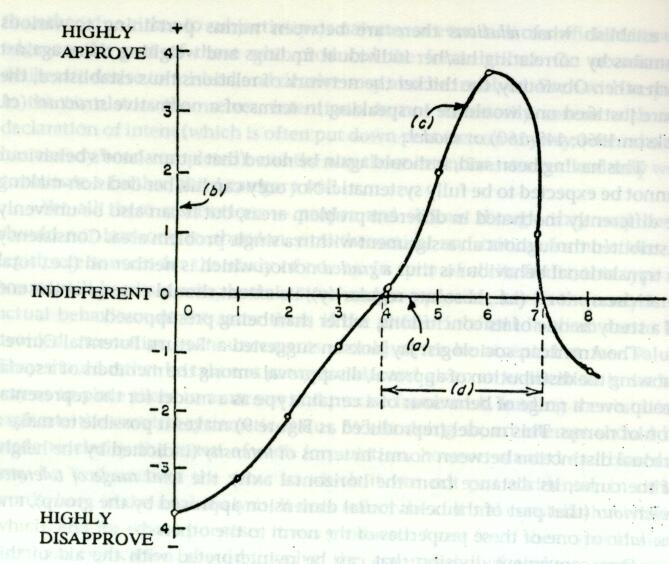

The American sociologist Jay Jackson suggested a 'Return Potential Curve',

showing the distribution of approval/disapproval among the members of a social

group over a range of behaviour of a certain type as a model for the representa-

tion of norms. This model (reproduced as Figure 9) makes it possible to make a

gradual distinction between norms in terms of intensity (indicated by the height

of the curve, its distance from the horizontal axis), the total range of tolerated

behaviour (that part of the behavioural dimension approved by the group), and

the ratio of one of these properties of the norm to the others.

One convenient division that can be re-interpreted with the aid of this

model is tripartite:9

(a) Basic (primary) norms, more or less mandatory for all instances of a

certain behaviour (and hence their minimal common denominator).

Occupy the apex of the curve. Maximum intensity, minimum latitude of

behaviour.

(b) Secondary norms, or tendencies, determining favourable behaviour. May

be predominant in certain parts of the group. Therefore common enough,

but not mandatory, from the point of view of the group as a whole. Occupy

that part of the curve nearest its apex and therefore less intensive than the

basic norms but covering a greater range of behaviour.

(c) Tolerated (permitted) behaviour. Occupies the rest of the 'positive' part of

the curve (i.e., that part which lies above the horizontal axis), and therefore

of minimal intensity.

9. Cf., e.g., Hrushovski's similar division (in Ben-Porat and Hrushovski 1974: 9-10) and its

application to the description of the norms of Hebrew rhyme (in Hrushovski 1971b).

68 DESCRIPTIVE TRANSLATION STUDIES AND BEYOND

Figure 9. Schematic diagram showing the Return Potential Model for representing norms: (a)

a behaviour dimension; (b) an evaluation dimension; (c) a return potential

curve, showing the distribution of approval-disapproval among the members of a

group over the whole range of behaviour; (d) the range of tolerable or approved

behaviour. (Reproduced from Jackson 1960.)

A special group, detachable from (c), seems to be of considerable interest and

importance, at least in some behavioural domains:

(c') Symptomatic devices. Though these devices may be infrequently used, their

occurrence is typical for narrowing segments of the group under study. On the

other hand, their absolute non-occurrence can be typical of other segments.

We may, then, safely assume a distributional basis for the study of norms:

the more frequent a target-text phenomenon, a shift from a (hypothetical)

adequate reconstruction of a source text, or a translational relation, the more

likely it is to reflect (in this order) a more permitted (tolerated) activity, a

NORMS IN TRANSLATION 69

stronger tendency, a more basic (obligatory) norm. A second aspect of norms,

their discriminatory capacity, is thus reciprocal to the first, so that the less

frequent a behaviour, the smaller the group it may serve to define. At the same

time, the group it does define is not just any group; it is always a sub-group of

the one constituted by higher-rank norms. To be sure, even idiosyncrasies

(which, in their extreme, constitute groups-of-one) often manifest themselves as

personal ways of realizing [more] general attitudes rather than deviations in a

completely unexpected direction.10 Be that as it may, the retrospective estab-

lishment of norms is always relative to the section under study, and no auto-

matic upward projection is possible. Any attempt to move in that direction and

draw generalizations would require further study, which should be targeted

towards that particular end.

Finally, the curve model also enables us to redefine one additional concept:

the actual degree of conformity manifested by different members of a group to a

norm that has already been extracted from a corpus, and hence found relevant

to it. This aspect can be defined in terms of the distance from the point of

maximum return (in other words, from the curve's apex).

Notwithstanding the points made in the last few paragraphs, the argument

for the distributional aspect of norms should not be pushed too far. As is so well

known, we are in no position to point to strict statistical methods for dealing

with translational norms, or even to supply sampling rules for actual research

(which, because of human limitations, will always be applied to samples only).

At this stage we must be content with our intuitions, which, being based on

knowledge and previous experience, are 'learned' ones, and use them as keys for

selecting corpuses and for hitting upon ideas. This is not to say that we should

abandon all hope for methodological improvements. On the contrary: much

energy should still be directed toward the crystallization of systematic research

methods, including statistical ones, especially if we wish to transcend the study

of norms, which are always limited to one societal group at a time, and move on

to the formulation of general laws of translational behaviour, which would

inevitably be probabilistic in nature (see Part Four). To be sure, achievements of

actual studies can themselves supply us with clues as to necessary and possible

methodological improvements. Besides, if we hold up research until the most

systematic methods have been found, we might never get any research done.

10. And see the example of the seemingly idiosyncratic use of Hebrew ki-xen as a trans-

lational replacement of English 'well' in a period when the norm dictates the use of

u-vexen (Chapter 4, Section 3).

References

Ben-Porat, Ziva and Benjamin Hrushovski. 1974. Structuralist

Poetics in Israel. Tel Aviv: Department of Poetics and

Comparative Literature, Tel Aviv University.

Ben-Shahar, Rina. 1983. Dialogue Style in the Hebrew Play, both

Original and Translated from English and French, 1948-1975. Tel

Aviv: Tel Aviv University. [Ph.D. Dissertation. Hebrew]

Even-Zohar, Itamar. 1975. "Decisions in Translating Poetry". Ha-

Sifrut/Literature 21. 32-45. [Hebrew]

Even-Zohar, Itamar. 1990. Polysystem Studies. Tel Aviv: The

Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics, and Durham: Duke

University Press. [= Poetics Today 11:1.]

Geest, Dirk De. 1992. "The Notion of `System': Its Theoretical

Importance and Its Methodological Implications for a Functionalist

Translation Theory". Harald Kittel, ed. Geschichte, System,

Literarische Übersetzung / Histories, Systems, Literary

Translations. Berlin: Schmidt, 1992. 32-45.

Harris, Brian. 1990. "Norms in Interpretation". Target 2:1.

115-119.

Hermans, Theo. 1991. "Translational Norms and Correct Translations".

Kitty M. van Leuven-Zwart and Ton Naaijkens, eds. Translation

Studies: The State of the Art. Proceedings of the First James S

Holmes Symposium on Translation Studies. Amsterdam-Atlanta, GA:

Rodopi, 1991. 155-169.

Holz-Mänttäri, Justa. 1984. Translatorisches Handeln: Theorie und

Methode. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia.

Hönig, Hans G. and Paul Kußmaul. 1982. Strategie der Übersetzung:

Ein Lehr- und Arbeitsbuch. Tübingen: Narr.

Hrushovski, Benjamin. 1971b. "The Major Systems of Hebrew Rhyme from

the Piyut to the Present Day (500 A.D.-1970): An Essay on Basic

Concepts". Hasifrut 2:4. 721-749. [Hebrew]

Izre'el, Shlomo. 1994. "Did Adapa Indeed Lose His Chance for Eternal

Life?: A Rationale for Translating Ancient Texts into a Modern

Language". Target 6:1.

Jackson, Jay M. 1960. "Structural Characteristics of Norms". Nelson

B. Henry, ed. The Dynamics of Instructional Groups:

Sociopsychological Aspects of Teaching and Learning. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1960. 136-163. [abridged version in:

Ivan D. Steiner and Martin Fishbein, eds. Current Studies in

Social Psychology. New Yrok: Holt, Reinhart & Winston, 1965.

301-309.]

Sheffy, Rakefet. 1992. Repertoire Formation in the Canonization

of Late 18th Century German Novel. Tel Aviv University. [Ph.D.

Dissertation.]

Shlesinger, Miriam. 1989b. "Extending the Theory of Translation to

Interpretation: Norms as a Case in Point". Target 1:1. 111-

115.

Snell-Hornby, Mary. 1988. Translation Studies: An Integrated

Approach. Amsterdam-Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Toury, Gideon. 1980a. In Search of a Theory of Translation.

Tel Aviv: The Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics, Tel Aviv

University.

Vodicka, Felix. 1964. "The History of the Echo of Literary Works".

Paul N. Garvin, ed. A Prague School Reader on Esthetics, Literary

Structure and Style. Georgetown University Press, 1964. 71-81.

[Czech original: 1942.]

Weissbrod, Rachel. 1989. Trends in the Translation of Prose

Fiction from English into Hebrew, 1958-1980. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv

University. [Ph.D. Dissertation; Hebrew]

Wexler, Paul N. 1974. Purism and Language: A Study in Modern

Ukrainian and Belorussian Nationalism (1840-1967). Bloomington:

Indiana University.